Explore these connections in Social Power and Institutional Power.

Discover their paths to power in Career Comparison.

Social Power

Institutional Power

Career Comparison

Timeline 1911–present

Governance in China

Interactive Map

Inside the Party

Getting Started

Index

The history of modern China begins with the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, ending more than 2,000 years of imperial rule.

Below are a few highlights from the past century.

Establishment of the PRC

Richard Nixon visits China

Tiananmen Square protest (June 4 Incident)

Governance in China

China’s central and regional governments manage a vast diversity of geographies, ethnicities, culture, economies, even political systems.

Throughout the system, the Communist Party controls the nation’s state apparatus, courts, military, resources and major industries through a parallel organization of Party committees, whose leaders wield the greatest power.

China is a nation of massive proportions, home to nearly a fifth of the planet’s population, and spanning 3.7 million sq. miles, making it one of the largest countries in the world. With 56 ethnicities inhabiting 33 regions, China represents a vast diversity of geographies, cultures, economies, and even political systems.

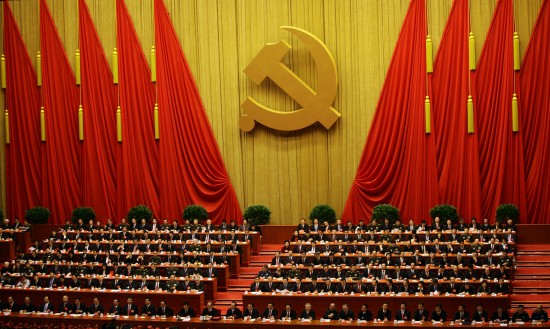

Delegates attend the closing session of the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, November 14, 2012. Credit:REUTERS/Jason Lee

Governing 1.3 billion people is no small task, and in China, the Communist Party is in charge.

While government and military institutions form the backbone of the state apparatus, the Party controls it, as well as courts, military, resources and major industries through a parallel organization of Party committees, whose leaders wield the greatest power.

According to the constitution, the State Council is the country’s cabinet and the highest executive organ of state power.1 But while the State Council implements many of the functions of government – crafting and implementing policies and regulations – its work is determined by the Party.

The country’s highest power is actually the Politburo Standing Committee, made up of seven Party leaders who also lead the nation’s top military and government bodies, their Party roles superseding their state roles. Little is known about the group’s inner workings.

It is in this context – behind-the-scenes Party control coupled with the varied needs of diverse, far-flung provinces – that governance in China takes place.

While previous leaders have focused on dismantling the worst excesses of central planning, the next generation must grapple with increasingly complex challenges – managing the difficult transition from a middle-income to high-income country, driving the exploration of space, building a global military presence while countering expansionist fears among its neighbors. Moreover, leaders face increasing pressures from within – from a yawning wealth gap to high-profile corruption scandals, to an aging society and calls for political reform.

Women wear traditional Uighur clothes wait for the start of the Olympic torch relay in Kashgar, Xinjiang province June 18, 2008. Credit:REUTERS/Reinhard Krause

Managing 1.3 billion people

There are 33 regions in China, each with populations rivaling European countries and a diversity of political agendas, ethnicities and economic arrangements.

Directly under the central government there are 22 provinces, as well as four municipalities (the large cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Chongqing), five autonomous regions (Xinjiang, Tibet, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia and Guangxi) and two Special Administrative Regions (Hong Kong and Macau). China also claims Taiwan as a province, though the island functions as a de facto independent state with its own government.2

The autonomous regions are made up of ethnic minorities, where according to the Constitution, the state’s regional head, the chairperson, is a “citizen of the nationality, or of one of the nationalities, exercising regional autonomy in the area concerned.”3 However, the Party secretaries of all five autonomous regions – who exercise the most control over the area – are all Han, the major ethnic group in China.4, 5 Under the “one country, two systems” policy, Hong Kong and Macau maintain their own economic and political systems as “special administrative regions,” enjoying greater autonomy than other parts of China.6

These regions are further divided into cities, counties and townships.

A villager votes during an election in Wukan, in China’s southern Guangdong province, March 3, 2012. Credit:REUTERS/Bobby Yip

The central government and the provinces

China’s 31 provincial-level Mainland regions have long been laboratories of governance, with local Party secretaries enjoying a significant degree of autonomy and power, cultivating their own public personas and promoting their own varying political agendas.

As China’s economy began to open up in the 1980s, the government designated special economic zones (SEZs) in Guangdong and Fujian with tax incentives, certain exemptions from import duty and other benefits. They proved to be the first of many. By the end of the decade, China added Hainan as its first provincial SEZ and further opened up 14 coastal cities, putting them in prime position to receive foreign direct investment.7

The result today is a vast difference in wealth between the coastal regions such as Shanghai and Tianjin and those inland like Guizhou and Gansu.

In addition to economic development, these coastal provinces have also seen more experimentation in social policy.8, 9

When arrests and intimidation failed to stop protests in a rebellious fishing community in southern China’s Guangdong province in late 2011, then-provincial Party secretary Wang Yang (汪洋) threw out the playbook that senior Communist officials routinely follow in dealing with grass roots protests.

Instead of unleashing a violent crackdown on the village of Wukan, in late-December Wang sent one of his senior aides to mediate a dispute over land seizures that had captured global attention. The aide, Zhu Mingguo (朱明国), helped broker a peaceful end to the three-month standoff between local authorities and villagers incensed at the death of a protest leader in custody.

Wang, a Politburo member who angled unsuccessfully for a seat on its standing committee, is an example of the wide berth of autonomy given to provincial-level Party secretaries – particularly those leading economic powerhouse regions such as Shanghai and Guangdong.

As of March 2013, six provincial-level Party chiefs also serve as members of the Politburo – those of the high-growth and politically important regions of Beijing, Guangdong, Tianjin, Chongqing, Xinjiang and Shanghai.

Only six out of 25 members have not served as Party chief of a province or municipality at some point in their career. Additionally, serving as a provincial-level Party chief has practically become a prerequisite for entrance into the Politburo Standing Committee – all but one of the current members have served in this role during their careers.

These leaders serve dual functions – they govern their regions with unmatched authority, but also serve as proxies for the central leadership.

Under China’s authoritarian system, leaders are not elected by citizens, freeing them from the sort of electoral pressure common in democratic political systems.

This leaves Party chiefs with “considerable latitude to define what provincial interests are according to their own preferences and calculations,” according to Hong Kong Polytechnic University scholar Lam Tao-chiu.10

The central authorities have a number of key checks to the autonomy of regional leaders, however. The Party’s Organization Department, not the local government, is responsible for appointing Party chiefs across the country, usually relocating them every three to seven years so they do not establish regional power bases.11 Central Party authorities can also investigate corruption in the provinces, giving them another means of local influence.12

China scholar Zheng Yongnian describes China’s existing political system as “de facto federalism,” writing that the provinces have become so decentralized that it is “increasingly becoming difficult, if not impossible, for the central government to unilaterally impose its will on the provinces.”13

Regions have their own revenue streams and local government spending now makes up the bulk of the country’s public expenditure.14 In 2011, local government spending accounted for 84.8 percent of the total government expenditure.15, 16

Despite efforts by the central government to exert political control over regions, rich provinces have the means to act more independently and resist central policy initiatives. On the other hand, regions with less economic power are too weak – economically and politically – to implement directives from Beijing, or initiate meaningful reform.17

Technically, all local governments are under the State Council, which sets policies, laws and tasks for the regions and which has the power to send auditors to check their accounts books.18, 19

The central government dictates policy on issues such as the economy, international diplomacy, national defense and population planning, while the regions take care of local infrastructure and local public security on their own.20 Other policies may be set by Beijing but are implemented locally.21 As special administrative regions, Hong Kong and Macau are granted more autonomy, and each has its own unique government structure and legal system.

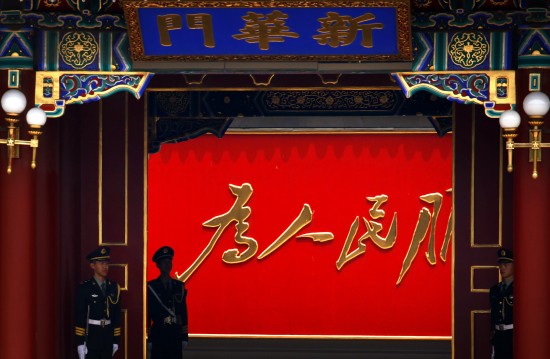

Paramilitary guards stand outside the Xinhua Gate of the Zhongnanhai leadership compound, the residence of Chinese President Hu Jintao, located in the centre of Beijing June 18, 2012.Credit:REUTERS/David Gray

Party and state

According to Richard McGregor’s “The Party”, around 50 top state companies are installed with “red machines”, a unique phone network offering secure direct lines to the desks of ministers, vice-ministers and heads of SOEs that he calls “a powerful symbol of the party system’s unparalleled reach, strict hierarchies, meticulous organization and obsessive secrecy”.22

Only top officials, state enterprise chairpersons, chief editors of Party newspapers and leaders of Party-controlled bodies have them, making the phones an exclusive network for the most elite leaders in China.23

One vice-minister told McGregor that more than half of the calls he received were from officials seeking favors, often jobs for family, friends and connections.24

Both the Party’s Central Committee and State Council are headquartered within the high walled, closely guarded, Zhongnanhai compound in the center of Beijing. Surrounding two lakes, it has been dubbed a modern day Forbidden City, China’s Kremlin, or the capital within the capital where the country’s leaders such as Mao Zedong (毛泽东) and Jiang Zemin (江泽民) have worked and lived.25, 26, 27, 28

The architecture of the Chinese government is designed to keep the Party omnipresent across every powerful organization in the country from the courts to the media and universities. An attempt by reformist former Party chief Zhao Ziyang (赵紫阳) to separate Party and state in the 1980s was never implemented after the 1989 government crackdown against pro-democracy protestors in Beijing, when senior leaders ousted Zhao from power.29

Major policy decisions are dictated by the Party and then implemented by the state or rubber stamped into law. The premier, who heads the State Council, also serves on the Politburo Standing Committee, as does the head of the legislature, the National People’s Congress. Almost all senior officials are Party members, meaning that the Party can punish them outside the courts through their own Discipline Inspection Commission.30

The Party maintains a presence in state-owned enterprises, government offices and military units through Party committees and leading Party members’ groups, giving it consistent voice through every major channel of power in the country.31

Although there is some division of labor – the Party takes the lead on policy, personnel and “matters of political principle” while the state handles the economy and social issues – the differentiation “enhances rather than undermines the party’s dictatorship,” according to Xiaowei Zang, author of “Elite Dualism and Leadership Selection in China”.32

According to Ming Xia, a professor from The College of Staten Island’s Modern Chinese Studies Group, Jiang Zemin, who became Party general secretary after the Tiananmen crackdown, set the overall guidelines for China’s governance after Zhao’s failed attempt to separate Party and state.

“The Party stands aloof, assumes overall responsibility and coordinates all sides of the government, congress, political consultative conference, and the masses organizations,” Xia wrote in the New York Times. “If the latter are the bones and fleshes of Chinese body politics, the Party is undoubtedly its brain, its nerve center and its sinews.”33

The National People’s Congress is supposed to preside over all administrative, judicial and procuratorial organs, as well as elect the president, chairman of the Central Military Commission and other top positions.34 But in reality, the Party drafts most legislation and passes it to the NPC for approval.35

About 70 percent of National People’s Congress delegates are Party members so “their loyalty is to the Party first, the NPC second,” according to a report by the BBC.36 According to a U.S. Congressional research report, the Party makes lists of nominees for deputies to the NPC “based in part on potential nominees’ perceived loyalty to the party” except at the most local level, namely the people’s congresses of townships and villages.37

According to a 2009 paper from the National University of Singapore’s East Asian Institute, 95 percent of leading civil servants at county level and above are Party members, and almost all top leaders in agencies and ministries are Party cadres.38

Meanwhile, the Party operates a United Front Work Department to manage relations with officially sanctioned groups, including religious organizations and the so-called eight democratic parties. The parties, however, have comparatively small membership and are not allowed to challenge the Communist Party’s leadership, with their heads instead accepting vice-chairman positions in the National People’s Congress.

Wan Gang (万钢), chairman of China’s Zhigong Party, became the first non-Communist Party minister since 1972 when he was appointed Minister of Science and Technology in 2007.39 He has a doctorate in mechanical engineering from Clausthal University of Technology in Germany and once worked at the German automaker Audi AG Corporation.

While the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference also exists for prominent outside groups to provide recommendations to the Party and the government, none of the suggestions are binding.40

The courts are officially subordinate to the legislature. At every level, government officials appoint judges while setting their budgets and salaries, making judges protective of the government, according to the Council on Foreign Relations, a U.S.-based policy think tank.41

The head of the Party’s Central Politics and Law Committee – not the chief justice – is actually the most powerful legal figure in China, overseeing the entire judicial branch, as well as the police and legislature.42 Meanwhile, the Party maintains its own disciplinary system, which it uses to investigate cases, arrest and detain people without going through the legal system.

State-owned enterprises are key contributors to China’s economy, and industries that the government believes are important to their economic and national security remain entirely or mostly under its control.43 By dominating key sectors such as oil, gas and telecoms, the government, and by extension, the Party, directly controls the flow of the nation’s wealth.44

Similarly, the People’s Liberation Army belongs to the Party, not the state.45 It remains subordinate to the Central Military Commission, which is headed by the Party general secretary (there are technically two CMCs – one that is under the state and another under the Party. However, they function as one organization and have the same members).

The Ministry of National Defense under the State Council does not play an active role in the PLA, instead mostly carrying out foreign military exchanges, according to China expert David Shambaugh.46

A villager looks at a picture of China’s President Xi Jinping, which hangs next to a banner in protest against a land acquisition project by the local government, in Sanhe village of Jinning county, Yunnan province April 16, 2013. Credit:REUTERS/Wong Campion

Key governance issues

The new leaders face a host of domestic challenges that now threaten the achievements made since the late 1970’s, a period in which annual economic growth has averaged around 10 percent.47

As China’s economy continues to grow, debate has grown over issues including income disparity, corruption, and the lack of reform, which the outgoing premier Wen Jiabao (温家宝) reiterated at a press conference after the closing meeting of the March 2012 National People’s Congress, the last before the leadership handover.48

The rich are getting richer as the breakneck economic growth of the last few decades has been funneled primarily to the government and business elite, according to Evan Feigenbaum, a senior associate at Carnegie’s Asia Program.49

In 2007, the 10 percent of people with the highest income earned 23 times more than the 10 percent who earned the least, compared to a ratio of 7.3 back in 1988.50

These vested interests are blocking further reform, which might curtail their ability to take advantage of their positions, according to Sun Liping, a sociologist who was academic advisor to Party general secretary Xi Jinping (习近平), during his doctoral studies at Tsinghua University.51

The problem is exacerbated by the lack of a competitive political process and free press, according to Minxin Pei, professor of government at Claremont McKenna College, who estimated in a 2007 paper that about 10 percent of government spending, contracts and transactions are used as kickbacks, bribes or is simply stolen.52

Meanwhile, China’s elderly population – already 13 percent of the population in 2010 – continues to grow, fuelled by the continuation of the one-child policy.53 How to provide social security as the elderly population peaks to an estimated 437 million by 2051 is a pressing question.54 By that time China’s workforce will have dropped from 72 percent to 61 percent of the population, perhaps signaling the end of China as a mass-manufacturing hub, according to the Economist.55

And for all the economic strides made by China, many of its minorities remain dissatisfied. Beside the ethnic Han majority, there are 55 other nationalities numbering approximately 106 million living in China, and a series of recent incidents of unrest and riots, particularly in Xinjiang and Tibet, have led to tight control of these regions.56, 57 By the beginning of 2013, more than 90 Tibetan monks, nuns and lay people had set themselves on fire to protest China’s rule in Tibet.58, 59, 60

China’s constitution promises freedom of religion, but many religious groups still claim persecution and repression.61, 62

Since 2011, China’s domestic security spending has exceeded its defense spending.63 In 2012, China’s “public safety” spending, including police, militia and other domestic security arms, reached 701.8 billion yuan ($111.4 billion), higher than the government’s reported 670.3 billion yuan ($106.4 billion) in defense spending.64

In a report jointly compiled with a top-level Chinese advisory council with the backing of then premier-in-waiting, Li Keqiang (李克强), the World Bank in March warned that China’s investment and export-led growth model had become unsustainable.65

Failure to bring about sweeping political and economic change would expose China to the risk of economic stagnation or crisis, it said.

The report called for new policies to boost the private sector, allow individuals greater freedom of movement, protect farmers’ land rights, stimulate innovation and creativity, enhance social equality, arrest grave environmental degradation, bolster a potentially unstable financial system and accelerate integration with the global economy.

Calls for change have found an audience among officials who worry the Communist Party has been treading water while risks mount that could threaten economic growth and, ultimately, Party rule.

“The problems that didn’t demand a solution before are becoming urgent,” said retired central government official Zhang Musheng in an interview with Reuters.

References

- 1 “The State Council,” GOV.cn, August 5, 2005.

- 2 “为什么说’台湾是中国不可分割的一部分’?,” Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council of the PRC, January 1, 2003.

- 3 “China’s Political System,” China.org.cn, accessed July 5, 2012.

- 4 “张毅,” The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China, last modified July 26, 2010, accessed July 6, 2012.

- 5 Cheng Li, “Ethnic Minority Elites in China’s party-state leadership: an empirical assessment,” China Leadership Monitor 25 (2008):2.

- 6 “Introducing Hong Kong,” Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office, London, accessed July 5, 2012.

- 7 Qinghua Zhang and Heng-fu Zou, “Regional Inequality in Contemporary China,” Annals of Economics and Finance 13 (2012):124.

- 8 Susan Lawrence and Michael Martin, “Understanding China’s Political System,” Congressional Research Service, May 10, 2012, 5.

- 9 Qinghua Zhang and Heng-fu Zou, “Regional Inequality in Contemporary China,” Annals of Economics and Finance 13 (2012):124.

- 10 Lam Tao-chiu, “Central-provincial relations amid greater centralization in China,” China Information 24 (2010):342.

- 11 Susan Lawrence and Michael Martin, “Understanding China’s Political System,” Congressional Research Service, May 10, 2012, 5.

- 12 Susan Lawrence and Michael Martin, “Understanding China’s Political System,” Congressional Research Service, May 10, 2012, 5.

- 13 Zheng Yongnian, “Power to dominate, not to change: How China’s central-local relations constrain its reform,” EAI Working Paper 153 (2009):1.

- 14 Tony Saich, “Governance and Politics of China,” 3rd ed. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), p. 200 in Susan Lawrence and Michael Martin, “Understanding China’s Political System,” Congressional Research Service, May 10, 2012.

- 15 “中央财政近年来切实增强基层政府财政保障能力 成效明显,” The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China website, March 8, 2012.

- 16 “2011年全国财政收入103740亿 财政支出108930亿,” China Economic Net, January 20, 2012.

- 17 Zheng Yongnian, “Power to dominate, not to change: How China’s central-local relations constrain its reform,” EAI Working Paper 153 (2009):2.

- 18 “Country paper: China,” United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, accessed 6 July 2012.

- 19 Susan Lawrence and Michael Martin, “Understanding China’s Political System,” Congressional Research Service, May 10, 2012, 5.

- 20 Zheng Yongnian, “Power to dominate, not to change: How China’s central-local relations constrain its reform,” EAI Working Paper 153 (2009):2.

- 21 Susan Lawrence and Michael Martin, “Understanding China’s Political System,” Congressional Research Service, May 10, 2012, 5.

- 22 Richard McGregor, The Party (London: Penguin, 2011), 8.

- 23 Richard McGregor, The Party (London: Penguin, 2011), 9.

- 24 Richard McGregor, The Party (London: Penguin, 2011), 10.

- 25 Nicholas Kristof, “Beijing Journal; Whatever the High Walls Hide, It Isn’t Opulence,” The New York Times, January 25, 1991.

- 26 Geremi Barme, “Walled Heart of China’s Kremlin,” Time, September 27, 1999.

- 27 David Pan, “Beijing’s real ‘Forbidden City,’” Asia Times Online, June 24, 2006.

- 28 David Pan, “Beijing’s real ‘Forbidden City,’” Asia Times Online, June 24, 2006.

- 29 Matthew Forney and Susan Jakes, “The Prisoner of Conscience: Zhao Ziyang, 1919-2005,” Time, January 16, 2005.

- 30 John Dotson, “The Chinese Communist Party and Its Emerging Next-Generation Leaders,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Staff Research Report (2012), U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, March 23, 2012.

- 31 John Dotson, “The Chinese Communist Party and Its Emerging Next-Generation Leaders,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Staff Research Report (2012), U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, March 23, 2012.

- 32 Xiaowei Zang, Elite Dualism and Leadership Selection in China (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004), 34.

- 33 Ming Xia, “The Communist Party of China and the ‘Party-State’,” The New York Times, accessed July 6, 2012.

- 34 “The Constitution of The People’s Republic of China,” GOV.cn, accessed July 6, 2012.

- 35 “Inside China’s ruling party: National People’s Congress,” BBC News, accessed July 6, 2012.

- 36 “Inside China’s ruling party: National People’s Congress,” BBC News, accessed July 6, 2012.

- 37 Susan Lawrence and Michael Martin, “Understanding China’s Political System,” Congressional Research Service, May 10, 2012, 25.

- 38 Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard and Chen Gang, “China’s civil service reform: an update,” EAI Background Brief 493 (2009):5.

- 39 “Observation: Non-communist personages as ministers,” People’s Daily Online, July 10, 2007.

- 40 Susan Lawrence and Michael Martin, “Understanding China’s Political System,” Congressional Research Service, May 10, 2012, 25.

- 41 Jayshree Bajoria, “Access to Justice in China,” Council on Foreign Relations, April 16, 2008.

- 42 Richard McGregor, The Party (London: Penguin, 2011), 24-25.

- 43 Andrew Szamosszegi and Cole Kyle, “An Analysis of State-owned Enterprises and State Capitalism in China,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, October 26, 2011.

- 44 Willy Lam, “China’s state giants too big to play with,” Asia Times Online, January 22, 2011.

- 45 Richard McGregor, “5 myths about the Chinese Communist Party,” Foreign Policy, January/February, 2012.

- 46 David L. Shambaugh, Modernizing China’s Military Progress, Problems and Prospects (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 124.

- 47 Minxin Pei, “Corruption Threatens China’s Future, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Policy Brief No.55, 2007.

- 48 “Wen says China needs political reform, warns of another Cultural Revolution if without,” XINHUANET, March 14, 2012.

- 49 Evan A. Feigenbaum, “Understanding China’s Economic Challenge and Why It Matters,” The Atlantic, February 28, 2012.

- 50 “我国贫富差距正在逼近社会容忍‘红线’,” XINHUANET, May 10, 2010.

- 51 David Bandurski, “Critical report pulled from China’s web,” China Media Project, January 12, 2012.

- 52 Minxin Pei, “Corruption Threatens China’s Future, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Policy Brief No.55, 2007.

- 53 “The Most Surprising Demographic Crisis,” The Economist, May 5, 2011.

- 54 “China faces the challenge of an ageing society,” people.com.cn, February 28, 2006.

- 55 “China’s Achilles heel,” The Economist, April 21, 2012.

- 56 “中国少数民族概况,” State Ethnic Affairs Commission of the People’s Republic of China, last modified April 27, 2007.

- 57 Cheng Li, “Ethnic Minority Elites in China’s Party State Leadership,” China Leadership Monitor No.25, 2008.

- 58 Edward Wong, “In Occupied Tibetan Monastery, a Reason for Fiery Deaths,” The New York Times, June 2, 2012.

- 59 “The Burning Issue,” The Economist, December 9, 2012.

- 60 “Full list of self-immolations in Tibet,” Free Tibet, accessed April 16, 2013.

- 61 “Constitution of the People’s Republic of China,” people.com.cn, accessed July 6, 2012.

- 62 Preetj Bhattacharji, “Religion in China,” Foreign Affairs, May 16, 2008.

- 63 Chris Buckley, “中国今年维稳预算6,244亿 首超军费,” Reuters, March 7, 2011.

- 64 “China domestic security spending rises to $111 billion,” Reuters, March 5, 2012.

- 65 “China 2030,” World Bank, February 28, 2012.

Inside the Party

China’s prosperous entry into the world economy prompted many Westerners to predict the end of communist rule. However, China remains a single-party state and the Communist Party of China wields influence in nearly all spheres of society.

In China, all roads lead to the Communist Party. China remains a single-party state and the Party is omnipresent – membership is crucial to careers in both the public and private sectors, leading many people to join for practical reasons.

Middle school students hold cardboards featuring the emblems of the Communist Party of China as they pose for photographs during an event to celebrate the party’s 91st anniversary, in Suining, Sichuan province June 30, 2012. Credit: REUTERS/China Daily

The Communist Party of China is the world’s largest political party, with more than 80 million members – approximately six percent of China’s population and roughly the entire population of Germany.1, 2

The nation’s most powerful leadership position is the Party general secretary – not the president or prime minister – and according to the country’s Constitution, the Party’s leadership “will exist and develop for a long time to come.”3, 4

The Party is front and centre in all areas of life, controlling the military, state, judiciary, key resources and major industries. Becoming a Party member means being part of an elite group that confers many benefits. However, the Party also enforces its own code of conduct, discipline and loyalty, wielding power through its Discipline Inspection Commission, which administers extrajudicial punishment to Party members with little public transparency.

Today’s Party

Despite predictions that China’s prosperous entry into the world economy would herald the end of communist rule, the Party is alive and well. But years of catastrophes and ideological shifts have made it far different from the party that was founded by a revolutionary band in 1921.5

The Party began as a small, leftist group of revolutionaries who sought to build a “classless society”.6 They defeated the ruling Nationalists, or Kuomintang, after a protracted civil war and in 1949 founded the People’s Republic of China. With Marxism-Leninism as its guiding ideology and Chairman Mao Zedong (毛泽东) at the helm, the Party instigated a number of radical campaigns. The Anti Rightist Movement of 1957 led to the persecution of thinkers and reformers. The Great Leap Forward (1958-1960) accelerated collectivism and set off years of chaos and mass famine, resulting in the deaths of tens of millions.7 The decade of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) saw a breakdown of society, with the closing of schools and institutions, which led to yet more leftism and persecution of intellectuals.

When Deng Xiaoping (邓小平) became paramount leader in late 1978, the Party’s priorities shifted to modernization and the opening up of the Chinese economy.8, 9 The Cultural Revolution was denounced and the Party line was retooled towards a more pragmatic “socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

Top leaders were poised to begin implementing political reforms, such as the separation of the Party and state and liberalization of the media, until the violent suppression of pro-democracy activists in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989 brought those discussions to a crashing halt.10, 11

By the time Jiang Zemin (江泽民) allowed private entrepreneurs into the Party in 2001, the same year China joined the World Trade Organization, the country was far from the Marxist ideal its forefathers envisioned.

Chinese wave the Party flags at the new airport construction site in

the southern city of Guangzhou to celebrate President Jiang Zemin’s

“three represents” political theory during an art performance, November

28, 2002. Credit: REUTERS/China Photo

“When the world looks back to the moment when the Chinese Communist Party finally embraced capitalism, this may be it,” the Far Eastern Economic Review declared after Jiang’s ‘Three Represents’ theory was officially announced at the Party’s 80th anniversary in 2001.12 The theory legitimized the Party’s expansion to include people from the country’s nascent private sector, opening the way for further privatization.

Today, China’s economy is capitalist in many respects, including the legal protection of private property rights, which was passed in 2007.13 However, major economic sectors, including energy and telecommunications, are monopolized by state-owned enterprises, led by government (and thus Party) appointees.14 The Chinese economic model helped the country weather 2008’s global financial crisis, but many questions have been raised over how to reform the economy further as growth cools in the coming years.15, 16

Toeing the line

Despite being constantly in flux, ideology still matters in China as a key way to legitimize the one-party state.17, 18

The Party requires millions of cadres nationwide to participate in “study campaigns,” where they study ideological Party theories propagated by leaders, such as former president Hu Jintao’s “scientific development” concept. Cadres study speeches and books and report their thoughts on what they’ve learned.19

The Party runs a network of thousands of Party schools across the country responsible for training officials, and attendance is a requisite stepping-stone for those climbing the Party hierarchy.20, 21

The most prestigious of these institutions is the Central Party School, which is located in northwestern Beijing, near the Summer Palace. Officials selected by the Central Organization Department and its regional branches are summoned there and are inspected for their future potential. Studying there is a sign of excellence and a way to move on to the Party’s fast track.22

There’s an old joke that circulates within the Party’s highly secured hallways: Where do you find the most careful driver in China? The Central Party School, because you never know who you might run into (or over) – anyone could be the future general secretary of the CPC.23

Such is the caliber of the roughly 2,000 cadres – including senior officials and managers of state-owned enterprises – who pass through its doors each year.24, 25, 26 They learn Party thought from Marx to Mao, Deng and Jiang, and social sciences such as economics, law and military affairs.27, 28

The school – which is also a think tank for the Party – serves as a forum for discussing new policies that allow the Party to convey its views to the Party’s rising stars on hot-button issues such as political reform, the role of NGOs and religious tolerance.

“The goal is to suck up an idea, defang it, and legitimize it for Chinese circumstances in a way that’s not threatening to the party,” Kerry Brown, a scholar working at Chatham House, told Foreign Policy. (Chatham House, a UK-based think tank, has hosted members of the school, according to the magazine.)29, 30 The school has also sent students to institutions worldwide including Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, Cambridge University and Copenhagen Business School,31 and runs a collaborative program with Yale University.32

In addition, the Party runs three national “executive leadership academies” for mid-level and senior cadres of the Party, governments, military, and state-owned enterprises, located at Jinggangshan , Yan’an and Pudong. Founded in 2005, the academies served to supplement Party schools in training Party members. Training usually serves as a prelude to and preparation for, a promotion.

Directed by the Party’s Central Organization Committee, which coordinates the staffing of official bodies nationwide, they also run public courses such as MBA and MPA programs.

Mid-level government officials dressed in red army uniforms stand next to a portrait of former Chinese leader Mao Zedong at an old house where Mao used to live, during a five-day training course at the China Executive Leadership Academy of Jinggangshan, in Jiangxi province September 21, 2012. Credit: REUTERS/Carlos Barria

The United Front

China has eight so-called “democratic parties” but they don’t interfere with the dominance of the Communist Party. According to the government’s official website, “the CPC is the sole party exercising political leadership in this system of multi-party cooperation,” which has been “generally accepted by various parties and people across the country after decades of practice.”33

The parties’ influence is limited and is “window dressing” that allows the government to say they listen to outside views, China observer Willy Lam told the BBC.34 Their membership rolls are comparatively minuscule, and they are barred from challenging the Communist Party’s leadership.35

Heads of the parties hold vice-chairman positions on the National People’s Congress or the Chinese People’s Consultative Conference (CPPCC), according to pro-Beijing newspaper Wen Wei Po.36 There have only been a handful of non-Communist Party ministers since China’s opening up – China Zhi Gong Dang (Party for Public Interests) chairman Wan Gang (万钢), became the first when he was appointed Minister of Science and Technology in 2007.

Still, internal factions exist within the Communist Party, which is viewed by analysts as a more likely catalyst for reform.37 The Party’s two most powerful factions, former Chinese leader Jiang Zemin’s so-called Shanghai Clique and Jiang’s successor Hu Jintao’s (胡锦涛) Tuanpai, have their own agendas and views about key political and economic reforms. However, the Party does not tolerate the public airing of these political differences and such fissures remain papered over for the public.

A hold on all areas

The power of the Party is built directly into the country’s governance structure.

Roughly based on the “hierarchical model of central control” developed by the Russian Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin, the Party ultimately makes decisions from the top and enforces them rigidly down the chain of command.38

The Party’s 25-member Politburo and its seven-man standing committee represent the apex of political power in China. Each Politburo member concurrently holds key positions in the central government, provincial-level leadership and the People’s Liberation Army, ensuring the Party retains influence over the main channels of power.39

Although little is publicly known about the Politburo’s internal machinations, it is believed to meet roughly once a month, with the Party releasing sporadic details about its discussions.40, 41 The body may meet to consider major policy shifts, handle extremely urgent issues, or legitimize a particular policy direction.42

The Politburo is elected by and responsible to the Central Committee, according to the Party’s constitution.43 But in practice, the makeup and policy decisions of the Central Committee are determined by the Politburo, according to Lawrence Sullivan, author of the “Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Communist Party.”44

Meanwhile, the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) is China’s top leadership body, made up of the top seven members of the Politburo, and makes decisions in all major policy spheres.45

No other Party or government body can overrule the PBSC, which increasingly operates according to “collective leadership” rather than the diktats of a single ruler.46

PBSC members typically lead all the major pillars of governance – including the Party, the State Council, the National People’s Congress, and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference – making it the key decision-making and operational body in Chinese politics.47

(The only time PBSC members do not hold the top state positions is during the transition period between the Party congress – usually held every five years in the autumn – when the new members of the Politburo Standing Committee are appointed, and the joint meetings of the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference held the following March, when those Party leaders take on their new state roles.)

Through the Central Committee, the Party operates departments that oversee personnel appointments, media, ideology, non-communist bodies, the judiciary, the police and civilian security, effectively preventing any autonomous power from challenging the Party’s dominance.48

The Central Committee also appoints the members of the Central Military Commission, the Party’s leading military body.49, 50 The general secretary of the Party typically serves as chairman of the CMC, which helps maintain Party control over the People’s Liberation Army.51

Smaller Party organizations also operate in enterprises, rural areas, government organs, schools, research institutes, and small neighborhoods.52, 53

People take their oaths in front of a Communist Party of China (CPC) flag during a ceremony to join the party at a park as part of celebrations marking the 90th anniversary of the party’s founding in Shanghai July 1, 2011. Credit: REUTERS/Aly Song

Joining the club

“Today’s Communist Party is a highly developed bureaucracy, like IBM or General Motors,” Columbia University scholar Andrew Nathan told The New York Times. “It’s not the Communist Party of Mao’s time.”54

The Party’s all-encompassing influence and embrace of the private sector has caused a surge of new members, with star students and entrepreneurs flocking to join.55 Membership is heavily male, with women making up less than one quarter of the Party’s 80 million members in 2011.56

Citizens are exposed to the Party early. The Young Pioneers, run by the Communist Youth League, is an organization for nearly all six to 14 year-olds.57 They learn about Communist ideals to “do as the Party says, love the motherland, love the people” and become the “heirs of communism,” according to the Young Pioneers’ constitution.58 It is also compulsory for them to wear a red scarf (honglingjin) every day at school to designate their membership in the Young Pioneers.

Joining the Communist Youth League between ages 14 and 28 is “an absolute must” for anyone seeking Party membership, according to Lawrence R. Sullivan, a political scientist, in the Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Communist Party.59, 60

The organization has been a launching pad and power base for many of the country’s top leaders, including Hu Jintao, a one-time CYL boss. The organization is also the recruitment base of the Tuanpai, one of the Party’s main factions and Hu’s power base.

Nearly all of the first secretaries of the youth league have also joined the Party’s Central Committee. The current chief, Lu Hao (陆昊), was appointed in 2008, one year after the 17th Party congress and was elevated to the Central Committee at the following Party congress in 2012.61

The organization mimics the power structure of the Party itself, with a congress every five years, a central committee and standing committee. It teaches its more than 75 million members Chinese communist thought and provides social services to young people such as assisting with exam study and helping them find jobs.62, 63

To join the Party, one must be over 18, introduced by two members and have their application discussed and approved by Party organs after background checks.64, 65 Prospective members attend study sessions and carry out community service.66 The Party will also recruit exceptional candidates.67 Probation is usually one year during which time limited membership dues must be paid.68, 69 Party members may not hold religious beliefs.70

After probation, members are part of an elite club. Membership is seen as a laurel, providing access to a career-advancing network. That explains the Party’s appeal to students; according to one study, college education is “by far the most important single predictor of party membership.”71

It could be a stepping-stone to a place in the civil service, which provides highly stable and prestigious jobs.72, 73 Membership also helps job prospects with state-owned enterprises and major firms.74 The crème de la crème may go to Party schools later, a key opportunity to network with movers and shakers in politics and business, who will all pass through its doors at some point in their careers.75

“Just as education is regarded as an investment in human capital, CCP membership can be regarded as an investment in what is sometimes termed political capital,” according to a paper from the University of Nottingham’s China Policy Institute.76

Party membership is pivotal to gaining guanxi – the deep personal connections that can smooth one’s rise to the top, whether in the government or private spheres. And in China, forging relationships with powerful mentors can alter the course of a person’s career.

To some analysts, conferring career benefits has helped the Party legitimize its rule.77 Just as red-hot economic growth has given the Party legitimacy to the masses, its ability to deliver material rewards to its most prized members proves its value to top achievers. This is even more important at a time when economic liberalization is rapidly creating more opportunities for Chinese citizens to create wealth and influence in the private sector, outside government jobs and state-owned enterprises.78, 79

The Party’s police

When it comes to crime and punishment, Party members are accountable to two authorities – the state and the Party. And as in so many areas of Chinese society, the Party’s rule supersedes the state.

The Discipline Inspection Commission, under the leadership of the Party’s Central Committee, is the Party’s in-house anti-graft body, empowered to investigate officials and detain them when necessary.80, 81 At least 800 full-time staff work in the west Beijing head office, while local commissions operate in the provinces under the dual leadership of the Party committees at the corresponding levels and the next higher commissions for discipline inspection.82

Officials wait outside the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection of the Communist Party of China’s office in Beijing September 20, 2007. Credit: REUTERS/Reinhard Krause

In recent years, the Party has said that combating corruption is a top priority, with 881,000 officials punished for misconduct from July 2003 to December 2008, according to Xinhua.83, 84 However, at a time when new millionaires emerge every year, many people now seek administrative positions precisely to monetize them.85

Officials in fields like customs, taxation, land sales and infrastructure development have discretion to select local businesses for lucrative work, and decide on regulations which affect those businesses’ bottom lines.86

The low salary of senior officials is another incentive for corruption.87 For example, Vice-Premier Wu Yi (吴仪) told Chinese business leaders in 2007 that her annual income totaled RMB120,000 (about $19,000).88 Some officials have even publicly complained about their low income.89

That has given rise to the so-called “black-collar class,” referring to corrupt officials whose cars are black, and shroud everything about their income, work and lives. “Everything about them is hidden, like a man wearing black, standing in the black of night,” Richard McGregor quoting an anonymous blog post in his book “The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers.”90

Those who run afoul of the Party are subject to shuanggui, or ‘double regulation,’ a CPC internal disciplinary measure that usually demands Party and government officials accused of wrongdoing to respond to charges or accusations against them at a designated time and place.

In China, senior Party officials cannot be arrested by civilian law enforcement bodies or other outside agencies for criminal offences until the Party’s Discipline Commission has investigated first.91 But to investigate an official, the commission needs to get approval from the Party organ at the next level above the official. That means the more senior a cadre, the more difficult for the commission to investigate, as senior leaders are able to protect their protégés, and other leaders don’t wish to anger a mentor by investigating his protégé.92

The use of extra-judicial shuanggui is designed to extract confessions93, 94, 95 via a shrouded Soviet-style disciplinary machine.96 Its hallmarks are isolation and harsh interrogation techniques, Flora Sapio, a visiting scholar at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, told The New York Times.97 The Dui Hua Foundation, a non-profit humanitarian organization in San Francisco, wrote that suspects are subject to simulated drowning, cigarette burns and beatings.98, 99

In the aftermath, suspects have committed suicide or died under mysterious circumstances. Peng Changjian, former deputy director of Chongqing’s Public Security Bureau, allegedly died of a heart attack during shuanggui detention.100, 101

Others are stripped of Party membership and wealth following their confessions, and handed over to government prosecutors for rubber-stamp trials that are closed to the public.102

“It’s as if you’ve fallen into a legal black hole. Once you are called in, you almost never walk out a free man,” Sapio said. She added that those in detention are not allowed to meet family members and do not have access to lawyers.103

Politicians who have experienced shuanggui include Chen Liangyu (陈良宇), the former Party chief of Shanghai, and Liu Zhijun (刘志军), former railways minister.

Naked officials

Corruption in the Party has given rise to hordes of ‘naked officials’ who send their family and money abroad and plan a getaway themselves.104 The phrase was coined in 2008 by Zhou Peng’an, a member of the China Democratic League and blogger in Anhui Province. Zhou’s blog post was later reprinted in the country’s mainstream media, including the websites of the Party’s flagship newspaper the People’s Daily and the official Xinhua News Agency.105, 106

A typical naked official is usually in his fifties, about to retire and with more than $13 million.107 China Economic Weekly, an economic magazine managed and sponsored by People’s Daily News Group, reported that since 2000, 18,487 officials have been caught allegedly trying to flee overseas.108

According to a confidential study of the People’s Bank of China in 2011, RMB800 billion had been moved out of China by officials between the mid-1990s and 2008.109

Top destinations for hoarding money are the US, Europe, Australia, Canada, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand.110 Foreign countries that have no extradition treaty with China are particularly favored by corrupt officials, said Li Chengyan, director of the Centre for Anti-Corruption Studies at Peking University.111

To prevent officials from fleeing overseas, the government has tried restricting travel abroad, confiscating passports, and requiring officials to register family members living overseas.112

In July 2010, a temporary regulation publicized by the central leadership required naked officials to provide written reports about the migration of their spouses and children to organization or personnel departments.113

In the same month, a national regulation said officials should make detailed annual reports about themselves, their spouses and children, on aspects including marital status, employment, income, properties, and investments, among other details.114

In January 2012, Guangdong Province announced that officials whose families have emigrated will probably not be promoted to high-level posts.115

However, officials have loopholes for the new measures, such as divorcing a spouse who lives overseas then remarrying,116 or holding multiple passports – the former governor of Yunnan Province Li Jiating was found to have five passports.117

“The big problem is that these officials are losing faith in the Chinese central government,” He Jiahong, a corruption expert at People’s University in Beijing, told the L.A. Times. “They are just taking care of their family and don’t care about China.”118

Updated March 14, 2013: This article has been updated to reflect that there have been several non-Communist Party ministerial-level officials since the opening up of China.

References

- 1 “国家统计局28日发布第六次全国人口普查主要数据,” china.com.cn, April 28, 2011, accessed June 26, 2012

- 2 “外媒: 中共党员人数与德国人口相当,” Xinhua, June 25, 2011, accessed June 26, 2012

- 3 Richard McGregor, The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers,(Penguin Books, 2011), 24

- 4 “Constitution of the People’s Republic of China,” The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 14 Mar 2004, accessed 10 October 2012

- 5 Gordon Chang, “The Coming Collapse of China: 2012 Edition,” Foreign Policy, December 29, 2011, accessed October 5, 2012

- 6 William A. Joseph, The Critique of Ultra-Leftism in China, 1958-1981, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1984), 6

- 7 “TIMELINE-The history of China’s Communist Party,” Reuters, 1 July 2011, accessed 19 July 2012 via Factiva

- 8 Patrick E. Tyler, “Deng Xiaoping: A Political Wizard Who Put China on the Capitalist Road,” The New York Times, February 20, 1997, accessed August 6, 2012

- 9 Ezra F. Vogel, “The Third Plenum, December 18–22, 1978,” in Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China, (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011), 600.6

- 10 赵紫阳, “关于党政分开”, Xinhuanet, accessed on September 24, 2012

- 11 钱钢, “读赵紫阳一九八九年五月六日谈话”, 中国改革网,February 26, 2010

- 12 Susan V. Lawrence, “Read China — Chinese Communist Party — The Life of the Party: President Jiang Zemin is throwing the doors of the Communist Party open to capitalists; His quiet revolution will allow private business to flourish — at a risk of even greater corruption,” Far Eastern Economic Review, 18 October 2001, accessed 18 July 2012 via Factiva

- 13 Susan Lawrence and Michael Martin, “Understanding China’s Political System,” Congressional Research Service, 10 May 2012, 7

- 14 Andrew Szamosszegi and Cole Kyle, “An Analysis of State-owned Enterprises and State Capitalism in China”, Economic and Security Review Commission, October 26, 2011

- 15 “China Model”, The Economist, accessed on September 25, 2012

- 16 World Bank, “China 2030: Building a Modern, Harmonious, and Creative High-Income Society”, February 27, 2012

- 17 Susan Lawrence and Michael Martin, “Understanding China’s Political System,” Congressional Research Service, 10 May 2012, 7

- 18 Frank Ching, “China’s Fluid Ideology,” The Diplomat, 4 August 2011, accessed 18 July 2012

- 19 Daniel Kwan, “Study campaign littered with political potholes,” South China Morning Post, 8 November 1999, accessed 18 July 2012 via Factiva

- 20 John Gapper, “Inside the Chinese Communist training school,” ft.com, 13 March 2012, accessed 8 October 2012

- 21 Rowan Callick, “The business of ideology in China,” The Australian, 11 June 2012, accessed 9 October 2012

- 22 Chen Xia and Yuan Fang, “Inside the Central Party School,” China.org.cn, 18 November 2007, accessed 18 July 2012

- sup>23 Chen Xia and Yuan Fang, “Inside the Central Party School,” China.org.cn, 18 November 2007, accessed 18 July 2012

- 24 David Shambaugh, “Training China’s Political Elite: The Party School System,” The China Quarterly 196 (2008): 831

- 25 “中共中央印发《2001-2005年全国干部教育培训规划》(全文)”, China.com.cn, accessed Oct.9, 2012

- 26 Xin Dingding, “Central Party School opens door to the media,” China Daily, 1 July 2010, accessed 18 July 2012

- 27 David Shambaugh, “Training China’s Political Elite: The Party School System,” The China Quarterly 196 (2008): 838

- 28 “China’s Central Party School Trains 50,000 officials in 30 years”, Peopledaily.com.cn, October 03, 2007

- 29 Dan Levin, “China’s Top Party School,” Foreign Policy, 6 March 2012, accessed 18 July 2012

- 30 Dan Levin, “China’s Top Party School,” Foreign Policy, 6 March 2012, accessed 18 July 2012

- 31 David Shambaugh, “Training China’s Political Elite: The Party School System,” The China Quarterly 196 (2008): 831

- 32 “Senior Chinese Government Leaders Program,” Yale Law School, 30 November 2011, accessed 14 August 2012

- 33 “[Democratic parties] Multi-party Cooperation and the Political Consultative System,” Gov.cn, accessed 18 July 2012

- 34 Michael Bristow, “China’s democratic ‘window dressing’”, BBC News, 5 March 2010, accessed 8 October 2012

- 35 Susan Lawrence and Michael Martin, “Understanding China’s Political System,” Congressional Research Service, 10 May 2012

- 36 刘凝哲, “8大民主党派党魁 将晋身国家领导人,” Wen Wei Po, 27 February 2008, accessed 8 October 2012

- 37 Richard McGregor, “5 Myths About the Chinese Communist Party,” Foreign Policy, January/February 2011, accessed 18 July 2012

- 38 Lawrence R. Sullivan, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Communist Party (Scarecrow Press, 2011), 5

- 39 Lawrence R. Sullivan, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Communist Party, (Scarecrow Press, 2011), 208

- 40 John Dotson, “The China Rising Leaders Project, Part1: The Chinese Communist Party and Its Emerging Next-Generation Leaders,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Staff Research Report (2012), 14

- 41 “十七届中共中央政治局会议” cpc.people.com.cn, accessed 17 September 2012

- 42 Kerry Dumbaugh andMichael F. Martin, “Understanding China’s Political System,” Congressional Research Service, December 31, 2009, 7

- 43 “Constitution of the Communist Party of China,” china.org.cn, accessed 1 September 2012

- 44 Lawrence Sullivan, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Communist Party (Scarecrow Press, 2011), 208

- 45 Lawrence R. Sullivan, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Communist Party (Scarecrow Press, 2011), 247

- 46 Cheng Li, China’s Changing Political Landscape: Prospects for Democracy, (Brooking Institute Press), 73

- 47 Andrew J. Nathen and Bruce Gilley, China’s New Rulers: The Secret Files, (New York Review of Books, 2002), 9

- 48 Lawrence R. Sullivan, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Communist Party (Scarecrow Press, 2011), 6

- 49 “Constitution of the Communist Party of China: Chapter III Central Organizations of the Party,” (中国共产党章程 第三章 党的中央组织), People.com.cn, October 25, 2007, accessed July 16, 2012

- 50 “The Organization of the Communist Party of China,” People.com.cn, last updated June 23, 2006, accessed July 16, 2012

- 51 Lawrence R. Sullivan, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Communist Party (Scarecrow Press, 2011), 7

- 52 “Constitution of the Communist Party of China: Chapter V Primary Organizations of the Party,” (中国共产党章程 第五章 党的基层组织), People.com.cn, October 25, 2007, accessed July 16, 2012

- 53 “The Leading Party Members’ Group and Party Committee of Organs,” (党组与机关党委), jgjy.gov.cn, accessed July 13, 2012

- 54 Elisabeth Bumiller, “Sometimes a Book Is Indeed Just a Book. But When?” The New York Times, 23 January 2006, accessed 14 August 2012

- 55 Richard McGregor, The Party: The secret world of China’s communist rulers, (Penguin Books, 2011), 31

- 56 “国家统计局28日发布第六次全国人口普查主要数据,” china.com.cn, April 28, 2011, accessed June 26, 2012

- 57 “The Constitution of the Young Pioneers,” (中国少年先锋队章程), 61.gqt.org.cn, July 12, 2007, accessed July 18, 2012

- 58 “The Constitution of the Young Pioneers,” (中国少年先锋队章程), 61.gqt.org.cn, July 12, 2007, accessed July 18, 2012

- 59 “中国共产主义青年团章程,” Xinhuanet, July 16, 2003, accessed August 7, 2012

- 60 Lawrence R. Sullivan, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Communist Party (Scarecrow Press, 2011), 296

- 61 “十八大政治局成员 呼之欲出,” United Daily News, June 23, 2012, accessed September 5, 2012 via Factiva

- 62 Hunter Hunt, “Joining the Party: Youth Recruitment in the Chinese Communist Party,” US-China Today, 11 July 2007, accessed 18 July 2012

- 63 Lawrence R. Sullivan, Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Communist Party (Scarecrow Press, 2011), 298

- 64 Simon Appleton, John Knight, Lina Song and Qingjia Xia, “The Economics of Communist Party Membership – The Curious Case of Rising Numbers and Wage Premium During China’s Transition,” 4, China Policy Institute, November 2005, accessed 18 July 2012

- 65 “Chapter 1: Membership, Constitution of the Communist Party of China,” Xinhuanet, accessed June 27, 2012

- 66 Simon Appleton, John Knight, Lina Song and Qingjia Xia, “The Economics of Communist Party Membership – The Curious Case of Rising Numbers and Wage Premium During China’s Transition,” 4, China Policy Institute, November 2005, accessed 18 July 2012

- 67 Simon Appleton, John Knight, Lina Song and Qingjia Xia, “The Economics of Communist Party Membership – The Curious Case of Rising Numbers and Wage Premium During China’s Transition,” 4, China Policy Institute, November 2005, accessed 18 July 2012

- 68 “Chapter 1: Membership, Constitution of the Communist Party of China,” Xinhuanet, accessed June 27, 2012

- 69 “关于中国共产党党费收缴、使用和管理的规定,” Xinhua News Agency, April 6, 2012, accessed June 27, 2012

- 70 Zheng Yi, “CPC members ‘must be atheist’,” Global Times, December 20, 2011, accessed June 27, 2012

- 71 Kjeld Erik Brodsgaard and Zheng Yongnian, The Chinese Communist Party in Reform, (New York: Routledge, 2006), 23

- 72 Hunter Hunt, “Joining the Party: Youth Recruitment in the Chinese Communist Party,” US-China Today, 11 July 2007, accessed 18 July 2012

- 73 Barbara Demick, “China’s Communists mull the party’s future,” Los Angeles Times, 1 July 2011, , accessed 18 July 2012

- 74 Hunter Hunt, “Joining the Party: Youth Recruitment in the Chinese Communist Party,” US-China Today, 11 July 2007, accessed 18 July 2012

- 75 John Gapper, “Inside the Chinese Communist training school,” ft.com, 13 March 2012, accessed 8 October 2012

- 76 Simon Appleton, John Knight, Lina Song and Qingjia Xia, “The Economics of Communist Party Membership – The Curious Case of Rising Numbers and Wage Premium During China’s Transition,” 6, China Policy Institute, November 2005, accessed 18 July 2012

- 77 Bruce J. Dickson and Maria Rost Rublee, “Membership Has Its Privileges,” Comparative Political Studies 33 (2000): 108

- 78 Xia Ming, “‘China Threat’ or a ‘Peaceful Rise of China’?”, The New York Times, accessed July 16, 2012

- 79 Bruce J. Dickson and Maria Rost Rublee, “Membership Has Its Privileges,” Comparative Political Studies 33 (2000): 88

- 80 “Constitution of the Communist Party of China: Chapter VIII Party Organs for Discipline Inspection,” (中国共产党章程 第八章 党的纪律检查机关), People.com.cn, October 25, 2007, accessed July 13, 2012

- 81 Richard McGregor, The Party: The secret world of China’s communist rulers, (Penguin Books, 2011), 137

- 82 “Constitution of the Communist Party of China: Chapter VIII Party Organs for Discipline Inspection,” (中国共产党章程 第八章 党的纪律检查机关), People.com.cn, October 25, 2007, accessed July 13, 2012

- 83 “推动反腐倡廉形势继续好转”,中国共产党新闻网, accessed on September 25, 2012

- 84 “1st Ld-Writethru: China punishes 881,000 officials in over five years,” Xinhua News Agency, April 22, 2009, accessed June 27, 2012

- 85 Richard McGregor, The Party: The secret world of China’s communist rulers, (Penguin Books, 2011), 140

- 86 Richard McGregor, The Party: The secret world of China’s communist rulers, (Penguin Books, 2011), 141

- 87 “当前腐败现象的承运级对策分析”, 中国共产党新闻网, May 8, 2009

- 88 “吴仪﹕明年「裸退」,请把我完全忘记!,” Ming Pao, December 25, 2007, accessed August 6, 2012

- 89 Richard McGregor, The Party: The secret world of China’s communist rulers, (Penguin Books, 2011), 140

- 90 Richard McGregor, The Party: The secret world of China’s communist rulers, (Penguin Books, 2011), 140-41

- 91 Richard McGregor, The Party: The secret world of China’s communist rulers, (Penguin Books, 2011), 137

- 92 Richard McGregor, The Party: The secret world of China’s communist rulers, (Penguin Books, 2011), 138

- 93 “A fine line between; fighting graft and; providing justice,” South China Morning Post, February 7, 2005, accessed July 9, 2012

- 94 Zhuang Pinghui, “Troubled drug agency’s deputy sanctioned,” South China Morning Post, June 5, 2010, accessed July 9, 2012

- 95 Choi Chi-yuk, “Another top official in Guangdong falls – Labour chief sacked as anti-graft drive goes on,” South China Morning Post, May 19, 2009, accessed July 9, 2012

- 96 Andrew Jacobs, “Accused Chinese Party Members Face Harsh Discipline,” The New York Times, June 14, 2012, accessed June 25, 2012

- 97 Andrew Jacobs, “Accused Chinese Party Members Face Harsh Discipline,” The New York Times, June 14, 2012, accessed June 25, 2012

- 98 “Official Fear: Inside a Shuanggui Investigation Facility,” Dui Hua Foundation, July 5, 2012, accessed September 5, 2012

- 99 Andrew Jacobs, “Accused Chinese Party Members Face Harsh Discipline,” The New York Times, June 14, 2012, accessed June 25, 2012

- 100 Andrew Jacobs, “Accused Chinese Party Members Face Harsh Discipline,” The New York Times, June 14, 2012, accessed June 25, 2012

- 101 “Officer linked to organized crime dies in detention,” South China Morning Post, September 19, 2009, accessed September 5, 2012 via Factiva

- 102 Andrew Jacobs, “Accused Chinese Party Members Face Harsh Discipline,” The New York Times, June 14, 2012, accessed June 25, 2012

- 103 Andrew Jacobs, “Accused Chinese Party Members Face Harsh Discipline,” The New York Times, June 14, 2012, accessed June 25, 2012

- 104 Barbara Demick and David Pierson, “China steps up efforts to keep officials from leaving country,” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2012, accessed June 27, 2012

- 105 “Origin of Naked Officials,” (裸官的由来), China.com.cn, last modified February 21, 2012, accessed July 5, 2012

- 106 “Blog: How Many Corrupted Officials Are Still Naked,” (博客:还有多少贪官在“裸体做官”), People.com.cn, last modified June 24, 2010, accessed July 5, 2012, originally on sina.com.cn, last modified July 3, 2008,

- 107 Barbara Demick and David Pierson, “China steps up efforts to keep officials from leaving country,” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2012, accessed June 27, 2012

- 108 “Supreme People’s Procuratorate: 18,487 fugitive officials caught in 12 year and 54.1 billion seized,” (最高检: 12年抓18487个在逃贪官 5年缴获541亿), People.com.cn, June 5, 2012, accessed July 13, 2012

- 109 Barbara Demick and David Pierson, “China steps up efforts to keep officials from leaving country,” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2012, accessed June 27, 2012

- 110 Barbara Demick and David Pierson, “China steps up efforts to keep officials from leaving country,” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2012, accessed June 27, 2012

- 111 “Moving the family abroad: Hedging their bets,” The Economist, May 26, 2012, accessed July 13, 2012

- 112 Barbara Demick and David Pierson, “China steps up efforts to keep officials from leaving country,” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2012, accessed June 27, 2012

- 113 “General Offices of the Central Party Committee and of the State Council require stronger management of civil servants whose spouses and children have moved overseas”, (中办国办要求对配偶子女均已移居国(境)外的国家工作人员加强管理), People.com.cn, last modified July 26, 2010, accessed July 13, 2012

- 114 “Regulations on self-declaration of personal issues of leaders and cadres,” (关于领导干部报告个人有关事项的规定), People.com.cn, last modified July 12, 2010, accessed July 13, 2012

- 115 “Guangdong proposes that in principle, officials whose families have emigrated will not occupy principal posts,” (广东拟规定家属已移居境外官员原则上不担任正职), China.com.cn, January 6, 2012, accessed July 13, 2012

- 116 Barbara Demick and David Pierson, “China’s exodus of the corrupt; Officials who move abroad with their ill-gotten gains pose a major challenge,” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2012, accessed June 27, 2012 via Factiva

- 117 “Perspective on the phenomenon of China’s corrupt officials fleeting,” (透视我国贪官外逃现象 (上篇)), People.com.cn, August 20, 2002, accessed July 13, 2012

- 118 Barbara Demick and David Pierson, “China steps up efforts to keep officials from leaving country,” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2012, accessed June 27, 2012

Getting Started

Not sure where to begin? Here are some videos and links to get you started.

The Connected China app showcases a wealth of information about China’s top leaders, key political and military bodies, and the informal factions and ideologies underpinning the system.

Key People

The Communist Party’s top officials exercise power in almost every sphere of Chinese society, from business to the military, judiciary and parliament.

The Politburo Standing Committee

Retiring Politburo Standing Committee members

These individuals have stepped down from the Politburo Standing Committee, but retain their state leadership positions until the next joint meeting of the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, scheduled for March 2013.

Key Party Organizations

Major policy decisions are driven Party organizations, not the state ministries or legislature.

- Politburo Standing Committee

- Politburo

- Central Committee

- Secretariat of the Central Committee

- Central General Office

- Central Organization Department

- Central Publicity Department

- Central International Department

- Central United Front Work Department

- Central Commission for Politics and Law

- Central Discipline Inspection Commission

Key State Organizations

The state apparatus implements the Party’s policies across a vast country of 1.3 billion people. These bodies are also led by key Party leaders, ensuring the Communist Party of China’s ultimate control.

- Presidency

- State Council

- National People’s Congress

- Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference

- Supreme People’s Court

- Supreme People’s Procuratorate

- State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission

Key Military Organizations

China has the largest standing army in the world, and its military leaders are historically potent political powerbrokers. Several powerful organizations represent the overlap of military and political clout in the mammoth force, about which very little is publicly disclosed.

- CPC Central Military Commission & PRC Central Military Commission

- CMC General Office

- PLA General Staff Department

- PLA General Political Department

Key Party Factions

While China remains a single-Party state, the Communist Party of China is carved into several cliques and factions behind closed doors, each with their own policy interests and entrenched leadership. The importance of guanxi and patron-client ties makes factional membership essential for climbing the Party ladder.

Key Ideologies

Today’s Communist Party of China has significantly evolved since its founding in 1921. Every leader since the Party’s founding has sought to introduce his own policies and leave a unique ideological legacy.

What else?

China has a long history and a complex political fabric. Here are some key terms, events and groups.

- Birth Control/One-child Policy/Family Planning Policy/Policy of Birth Planning

- Danwei

- Eight Elders (Eight Immortals)

- 50-cent Party

- Generations of Chinese Leadership

- Guanxi

- Hukou

- Lianghui or “two sessions”

- Mishu

- Party Committee

- Privileged Supplies (tegong)

- Reform and Opening Up

- Secretary

- State-owned enterprises

- The Left and The Right

- Within the system

- Rusticated Youth or Sent-down Youth (zhiqing)

- Zhongnanhai

Video Tutorials

China 101 + Featured Stories

Social Power View

Institutional Power View

Career Comparison View

Index

For desktop users, use the search function (CTRL+F for Windows; ⌘+F for Macs) to find key people and organizations

Connected China showcases a wealth of information about China’s top leaders, as well as key political, governmental and military bodies.

People

Ai Weiwei Outspoken social critic and China’s most famous contemporary artist

Bao Tong Former political secretary of Zhao Ziyang and former director of the Party’s Political Structure Reform Research Centre

Bateer Governor and deputy Party chief of Inner Mongolia

Bayanqolu Governor and deputy Party chief of Jilin, and member of the Party Central Committee

Bo Xilai Disgraced former Party chief of Chongqing, former member of the Politburo and of the Central Committee

Cai Wu Minister of Culture and member of the Central Committee

Cai Yingting Commander of the Nanjing Military Region

Cao Gangchuan Former vice-chairperson of the Central Military Commission and former minister of National Defense

Chang Wanquan Member of Central Military Commission, state councilor and Minister of National Defense

Chang Xiaobing Chairman of China United Network Communications Group Co Ltd

Chen Bingde Former member of the Central Military Commission and chief of the PLA General Staff

Chen Deming President of the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits and CPPCC standing committee member

Chen Esheng Chairman and temporary Party chief of China Sinolight Corporation

Chen Guangcheng Activist for victims of illegal birth control abuses

Chen Guoling Vice-chairman of the National People’s Congress Overseas Chinese Affairs Committee

Chen Hongsheng Chairman of the China Poly Group Corporation

Chen Lei Minister of Water Resources

Chen Liangyu Former Shanghai Party chief and Politburo member sentenced to 18 years in jail for bribery and abuse of power in 2008

Chen Min’er Governor and deputy Party chief of Guizhou

Chen Quanguo Party chief of Tibet

Chen Wu Chairman of Guangxi Autonomous Region

Chen Yuan Vice-chairman of the CPPCC National Committee, son of one of the Party’s Eight Immortals Chen Yun

Chen Zhenggao Governor and deputy Party chief of Liaoning

Chen Zhili Former State Councilor and former minister of education

Chen Zhu Chairman of the Chinese Peasants’ and Workers’ Democratic Party and vice-chairman of the National People’s Congress

Chi Haotian Former Politburo member (1997-2002)

Chu Yimin Political commissar of the Shenyang Military Region

Chui Sai-On, Fernando Chief executive of the Macau Special Administrative Region government

Cui Dianguo Chairman of China CNR Corporation Limited

Dai Bingguo Former state councilor (2008-2013)

Dalai Lama Spiritual leader of the Tibetan people, former head of state of Tibet, and Nobel Peace Prize recipient in 1989

Deng Changyou Vice-chairman of the National People’s Congress Internal and Judicial Affairs Committee

Deng Xiaoping (d. 1997) Former paramount leader of China

Ding Guangen (d. 2012) Former Politburo member (1992-2002)

Ding Zilin Leader of activist group Tiananmen Mothers

Du Hengyan Political commissar of the Jinan Military Region

Du Jiahao Deputy Party chief and acting governor of Hunan

Du Qinglin Member of the Secretariat of the Central Committee and vice-chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference

Fan Changlong Vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission and Politburo member

Fang Fenghui China’s top general — chief of the PLA General Staff, Central Military Commission member

Fang Lizhi (d. 2012) Astrophysicist and pro-democracy campaigner

Fu Chengyu Chairman of China Petrochemical Corporation and chairman of China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation

Fu Yuning Chairman of the China Merchant Group and chairman of the China Merchants Bank

Gan Yisheng Standing committee member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference

Gao Hucheng Minister of Commerce

Gao Zhisheng Leading human rights lawyer

Geng Huichang Minister of State Security

Gong Jingkun Chairperson and Party chief of Harbin Electric Corporation

Guo Boxiong Former vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission and former Politburo member (2002-2012)

Guo Gengmao Party chief of Henan Province

Guo Jinlong Politburo member and Party chief of Beijing

Guo Shengkun State councilor and Minister of Public Security

Guo Shuqing Deputy Party chief and acting governor of Shandong

Han Changfu Minister of Agriculture and member of the Central Committee

Han Qide Chairperson of the Jiu San (Sept. 3rd) Society and vice-chairperson of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference

Han Zheng Politburo member and Party chief of Shanghai

Hao Peng Governor and deputy Party chief of Qinghai

He Guoqiang Former top anti-graft official and former Politburo Standing Committee member (2007-2012)

He Yong Former deputy secretary of the Party’s Central Discipline Inspection Commission and former member of the Party’s Secretariat

He Yu Chairman and Party chief of the China Guangdong Nuclear Power Holding Corporation

Hu Chunhua Politburo member and Party chief of Guangdong

Hu Jia Activist for the environment, AIDS victims, democracy and human rights

Hu Jintao China’s sixth president, former Party general secretary and former chairman of the Central Military Commission

Hu Maoyuan President and Party chief of the Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation (Group)

Hu Yaobang (d. 1989) Liberal former Party general secretary (1980-1987); seen as too liberal and sacked as Party chief by conservatives

Hua Guofeng (d. 2008) Successor to Mao, former Party chief (1976-1981) and premier (1976-1980), major decision-maker in removing the Gang of Four

Hua Jianmin President of Red Cross Society of China

Huang Ju (d. 2007) Former Politburo Standing Committee member (2002-2007) and former vice-premier (2003-2007)

Huang Qifan Mayor and deputy Party chief of Chongqing

Huang Shuxian Minister of Supervision and deputy secretary of the CPC Central Commission for Discipline Inspection

Huang Xingguo Mayor and deputy Party chief of Tianjin